Trevor Baylis interview from the Swimming Times

6 March 2018He was best known as an award-winning inventor but Trevor Baylis, who died at the age of 80 on 5 March 2018, was also a former international swimmer, stunt diver and swimming pool salesman.

Swim England’s magazine, Swimming Times visited Trevor in May 2015 and here we look back at the article in tribute to the man who invented the clockwork radio.

An extraordinary home

Trevor Baylis’s directions offered the first clues about his extraordinary home. ‘Turn left down Water Lane, head for the footbridge to Eel Pie Island and I’ll meet you on the bridge,’ he said.

As I headed down the aptly-named Water Lane, a large flock of gulls, geese, ducks, swans and coots contested the food scraps being thrown by passers-by. Nearby a row of parked cars looked in imminent danger from the rising waters of the tidal Thames. Trevor is among those who’ve been caught out by occasional high tides and it led to a £600 repair bill for his car.

My interviewee was on the footbridge as promised, and in the two or three minutes it took to walk to his garden gate, no less than five people offered a cheery ‘Hello, Trevor.’ Here, clearly, was a man both well-known and popular in his own backyard.

And what a backyard. The home of the inventor and former swimmer, stunt diver and swimming pool salesman is one of a few dozen houses clustered tightly together on Eel Pie Island at Twickenham, south-west London – a community once described as ‘50 drunks clinging to a mudflat’ and where the Rolling Stones played gigs before they were famous. Apparently it takes its name from a maker of eel pies, whose customers included Henry VIII as he sailed to Hampton Court.

These days there’s barely room to swing a cat between Eel Pie Island’s houses but who wants to swing cats when the waters of the River Thames lap your garden? Besides, Trevor’s only pet is a dog not a cat. And to think that this most sought-after of building plots was bought 45 years ago with the proceeds of 18 days’ work.

Not just any work, though. In 1970 Trevor spent two-and-a-half weeks in West Berlin as the star of an underwater escapology stunt in which an Egyptian pharaoh was lowered in a sarcophagus into 14 feet of water. Trevor played the pharaoh and the trick nearly cost him his life on one occasion. But he was paid danger money and some. ‘I’ve always been a showoff – or a showman,’ he says. ‘When I was selling swimming pools, I would do somersaults to conjure the crowd. I loved doing crazy diving.’

‘What do you mean by crazy diving?’ I asked.

‘You run along and put your arms and legs up. When I did the shallow water trick, I wore an old-fashioned costume and did a belly-flop to spread the load. I never went higher than the 5m board for my crazy diving. But I did used to jump from the 5m to the 3m and into the pool. It’s a wonder I didn’t break my neck.’

The Berlin Deutscheshalle

During his 18 days as a circus escapologist in the Berlin Deutscheshalle, Trevor did 36 performances and was paid £350 a day – several times what most people earned in a year. ‘That was big money in those days. It was enough for me to buy a plot of land and build the house of my dreams. I had a mortgage as well but the money from Berlin bought the plot.’

‘It’s not a big house but what would it be worth today? A million pounds?’ I asked.

‘Something like that.’

Trevor designed the house himself and he and his then girlfriend built much of it with their own hands – and a more eccentric home would be hard to find. It has the designer’s background and personality written on every brick. On entering, you step not into a hallway or lobby but the inventor’s L-shaped workshop, which extends along two sides of the house. It’s total length is about 15 metres and almost every centimetre of wall space is occupied by the nuts and bolts of Trevor’s trade – tools and gadgets of every shape and size. ‘I never throw anything away,’ he admitted. This was evident.

Passing through the next door, you step not into a living room but a swimming pool, its blue cover extending within inches of three of the four walls, the walls themselves decorated with wetsuits and other aquatic paraphernalia. Trevor is a vociferous advocate that everyone should be able to learn to swim.

Between the pool and the remaining wall, a pathway leads – at last – to an area of relatively normal living space. Like those of the workshop and pool, the walls of the combined living room and kitchen are fully occupied – not with gadgets and tools, not with aquatic kit, but with memorabilia from the 77-year-old’s long and remarkable life.

‘Do you know who she is?’ asks Trevor, referring to a photograph showing him in a warm embrace with a beautiful woman. ‘That’s Lorraine Chase.’

This Is Your Life

Nelson Mandela and Michael Aspel were among the others that caught my eye, not to mention the famous red book presented by Aspel to Trevor when he appeared on This is Your Life in 1997. Nelson Mandela’s support helped propel Trevor’s most famous product into the invention stratosphere. His clockwork radio was inspired by a television programme, which suggested that the spread of AIDS across Africa could only be halted by education and information through radio broadcasts.

The hand-powered radio, which featured on Tomorrow’s World and works without electricity or batteries, won national and global design awards and also led to the wind-up torch. The invention led to the award of the OBE, which he received from the Queen in 1997. In 2015, he was appointed CBE in the New Year Honours for ‘services to intellectual property’ – a reference to his dedicated campaign to protect the rights of inventors whose patented creations are copied by manufacturers in other parts of the world.

At the far end of Trevor’s living room, sliding glass doors open onto the next startling feature of this extraordinary home – an astro-turfed garden lapped by the waters of the Thames. But this is Eel Pie Island’s equivalent to the dark side of the moon – the quiet side, out of sight of Twickenham’s busy shoreline and devoid of passers-by save for the occasional rower and the more frequent pleasure craft which motor past in spring and summer.

Trevor’s garden doubles as a wharf and a couple of boats are moored there. You would expect that but a more unlikely sight, parked incongruously between house and river, is an old red car that has seen better days. ‘When I built this house, I thought it would be rather groovy to make a car that looked like a 1920s or 1930s model but was actually a modern car,’ he explains. ‘I built the chassis and bodywork but it has a Ford Cortina engine.’

‘I don’t think it will pass its MoT,’ I said. The owner did not disagree.

The best of the house was yet to come. Alongside the staircase to the upper floor, a large window affords a perfect view of the swimming pool. The bedroom doubles as an office and again the walls are lined with Baylis memorabilia – including his 1950s swimming medals in a frame. Another pair of sliding glass doors opens on to the roof garden, complete with barbecue, hot tub and ‘lazy lawn’, as Trevor calls the Astroturf, not to mention another view over the Thames.

Wartime London

The seeds of his life and career as an inventor and aquatic stuntman were sown during his childhood in wartime London. He says he ‘became an engineer’ at the age of five after his father bought him a Meccano set. With the schools closed because of bombing raids, he also enjoyed swimming in the Grand Union Canal – despite getting covered in dung from the horses that pulled the barges in those days.

Later he and his friends would meet up for a swim at a local pool before going on to their schools. He was repeatedly caned for arriving late – until the local press turned up to photograph him after a swimming achievement. At that point the headmaster claimed some credit, saying, ‘We knew Trevor could do it!’

He swam for Heston SC, Middlesex, Southern Counties and Great Britain and, during his national service, for the Army and Combined Services. The Middlesex and Southern Counties backstroke champion also came second in the ASA National Championships a couple of times. His highly entertaining autobiography Clock This, published in 1999, includes a detailed account of the 1953 British junior 110yds backstroke final at Blackpool’s Derby Baths, where Trevor and Bristol’s Derek Davies clocked the same time, only for Davies to be given the verdict after a long delay. The bronze medal went to Coventry’s Graham Sykes, who went on to reach the Olympic final in Melbourne three years later. Trevor, who also played water polo for Ealing, rates his failure to qualify for the 1956 Games as his greatest disappointment.

Very light physique

He believes his physique was his biggest handicap. A coach at a national training camp for Olympic hopefuls under chief trainer Max Madders at Loughborough College in 1953 commented: ‘Fast stroke. Head rather high and feet rather low. Some good promise here. Very light physique.’ Trevor say: ‘That last phrase just about summed up why I never made it to the Olympics. A swimmer with a strong physique generating more power will generally beat a smaller opponent.’

Trevor also cut his teeth as a stunt diver at Heston Baths, where he and his friends would try to outdo each other with ever more complicated dives from the 3m board. He and a couple of mates later former the Aqua Crackers, a comedy diving act, which performed various stunts from the 3m and 5m boards. It was good training for his later roles as a circus performer and stunt double.

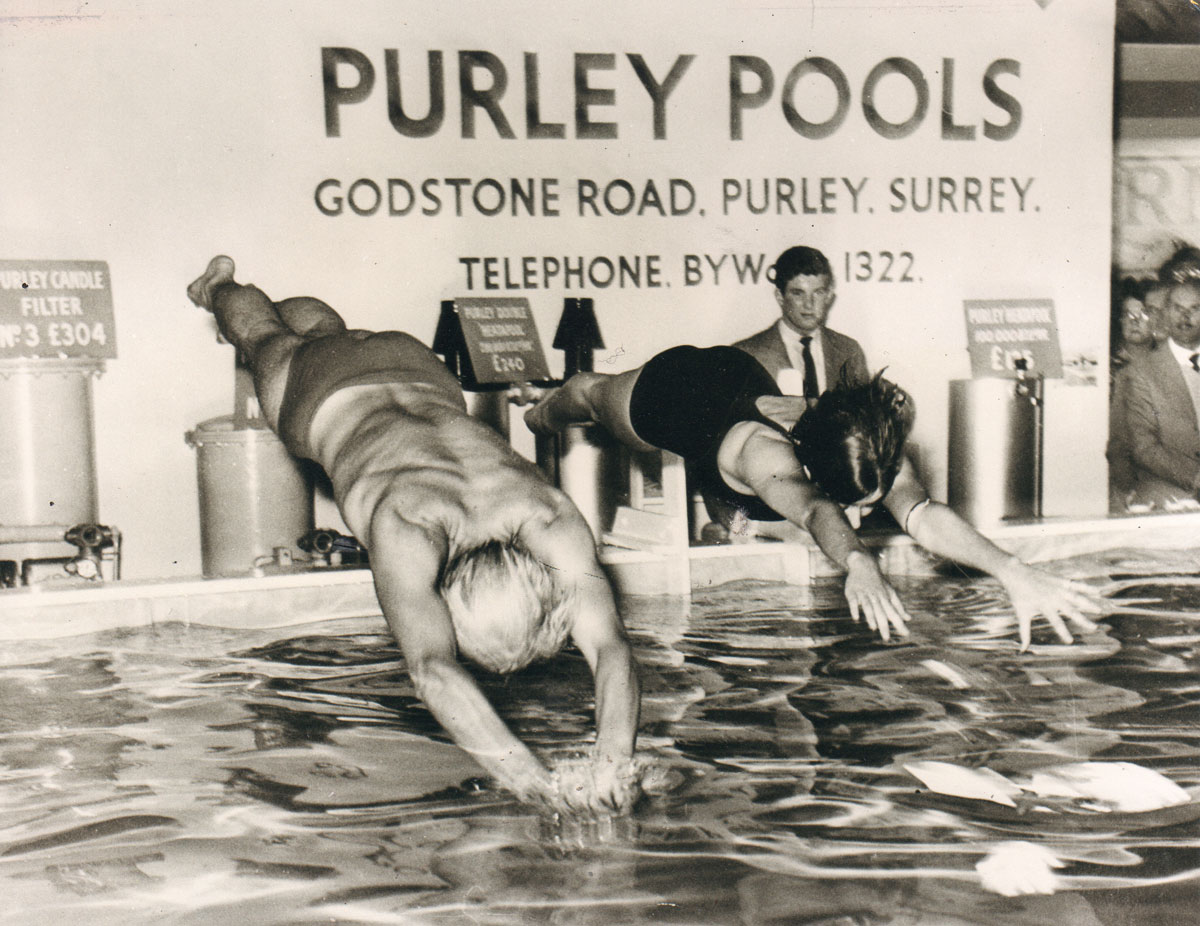

Trevor’s eight-year stint as a salesman for Purley Pools in the 1960s enabled him to use his two great talents – swimming and engineering. The Surrey company made the first freestanding PVC-lined swimming pools and travelled the country selling them to schools, local authorities and well-off families. During a quiet day at the Ideal Home Exhibition in 1963, Trevor took a dip. He was about to climb out when his boss told him: ‘Don’t get out – we’ve started to sell swimming pools.’

He expanded his role to include tricks and dives, which proved so popular that exhibitions started offering the company cheap space in exchange for Trevor’s swimming and diving displays. They went down well everywhere except the Chelsea Flower Show, where an official halted the show, claiming it was ‘undignified’, ‘unsuited to the ambience of the show’ and that people had complained about being splashed. Back at base, Trevor used his engineering skills to devise dozens of improvements to the pool technology.

By the mid 1960s, he also had his own company, Shotline Displays, which performed aquatic stunt shows around the country and abroad using a 10,000-gallon tank of his own construction. This led in the late 1960s to stunt work for TV shows with Dave Allen, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore and illusionist David Nixon. The Pete and Dud stunt was a send-up of a more serious escape routine from a submerged car. The idea is not to panic but to wait for the water pressure inside the car to equal the pressure outside, which makes it easy to open the door. ‘But Dud, trapped by his seatbelt and being a foot shorter than Pete, would be half-drowned long before the water reached the required level,’ says Trevor, who was hovering underwater with an air line in case Dud needed resuscitation.

The money earned in Berlin also enabled Trevor to start his own swimming pool company, Shotline Pools, installing steel-walled pools around the country. A sideline was supplying total immersion christening pools for Baptist churches. ‘Every hour I wasn’t putting in swimming pools, I was back on Eel Pie Island building my house or doing swimming and diving stunt work,’ he says. ‘I also serviced pools. I was working so hard, I didn’t have time to be tired. But I loved every minute.’

In those days they used to hold a swimming race around the island with the footbridge as the start and finish line. Always the maverick, Trevor checked the rules and opted to swim in the opposite direction to all the other swimmers. It meant swimming against the tide in the early stages but an easy cruise later on. He won. He says his tactics reflected his philosophy on life: ‘Get the strenuous bits out of the way, then lie back and enjoy the easy bits.’

Trevor Baylis was, born 13 May 1937 and died on 5 March 2018

Swim England

Swim England